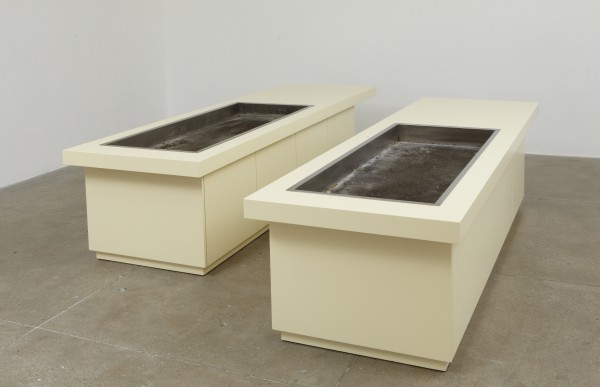

The last of three looks at the practices of Colin Snapp and Daniel Turner (together known as Jules Marquis), here I talk with Turner, whose solo work draws as much from minimalism as Snapp’s does from conceptual photography. Turner’s work has evolved in fascinating ways since we last spoke; his current show, now on view at Franklin Parrasch in New York, features a set of industrial kitchen sinks set into long counters, each filled with a sort of primordial goo that will ultimately dissolve through the surrounding metal. While he is still concerned with the ephemeral nature of basic elements, Turner has here drawn from a more explicit set of cultural markers then the steel wool and polyethylene of past projects. The works are less site-specific than in the past, and much more about (and engaged with) contemporary experience. Read our recent conversation below.

You work has always, to me, investigated the nature of basic elements – how and when they change, and the kinds of marks they leave behind. There’s a marked tension between presence and absence, which is something you’ve talked to me about in the past. How does this new body work fit into that dialogue? It seems that these sculptures are more grounded, and present, than your past work. These works are in fact more physically grounded, but are by no means anymore significant or more apparent than the past works, which were highly temporal in nature. The pieces in question contain stainless bays that will continue to erode through and after the exhibition has taken place. Over time the dependency of my work on the exhibition space became somewhat problematic – a formula had emerged – so I had to push for my own arena. These new works are the start of this push.

If the spaces in which you were exhibiting overly conditioned the formal and conceptual nature of your practice, did this push out move you further away from the pictorial? Is this something you continue to be concerned with? The steel rubbings left distinct visual marks, placing them in a relatively traditional, if time-sensitive, relationship with the viewer, one that these eroding bays certainly exist outside of. This idea of picture making I rarely think of; I abandoned stretcher bars long ago. However, it did lead me towards considering architecture and the bodies relationship to space. So to answer your question: Yes, the current works have once again pushed me beyond the pictorial.

What led you to choose these particular architectural forms (the counters and sinks)? Is there a particular relationship between bodies and these forms in space (whatever space that might be – a gallery or an industrial kitchen) that you’re excavating? The vocabulary emerged while working in a defunct office kitchen that served as a studio a few years ago. At that time I came to recognize industrial manufacture and its own psychology as something my work was beginning to lean towards. For the past century home economists and industrial engineers have crossed pollinated, coming up with concepts such as the work triangle, theories on the way the body functions in domestic environments, and Taylorism, the theory of management that analyzed and synthesized workflows. After realizing my first works in this series, titled Britannica, I soon after stripped the work of its own domestic makeup – scaling the architecture down and emphasizing a more agricultural or industrialized approach.

What I find fascinated about this idea, and maybe you had no intention of making work that dealt with these terms, is that some artistic production now operates in the same way, and sometimes on the same scale, as industrial production – Koons and Murikami, Roth and McCarthy, etc. Is this hands-off, factory-line way of making art of interest to you? Or are you drawn more to the material qualities of industrial production, in the same way Finish Fetish artists were drawn to the smooth lines and paint jobs of California car culture? The latter, although I’m not opposed to the scale of production these artist are working with – in fact I find the labor fascinating. What’s interesting to me in terms of the artists you mentioned would be an actual critique of applied discipline, (i.e.: production), and less of what is actually produced. I share a great affinity towards Finish Fetish but also towards a brutish touch. I can’t say that I favor one over the other, and try to consider any given material or surface’s commercial, timing or contextual implications.

Where do you see your practice taking you next? That’s actually a difficult question to answer, but I can tell you it will go nowhere If I fail to continually criticize it.

Daniel Turner

Through April 27

Franklin Parrasch Gallery

20 West 57 Street

New York