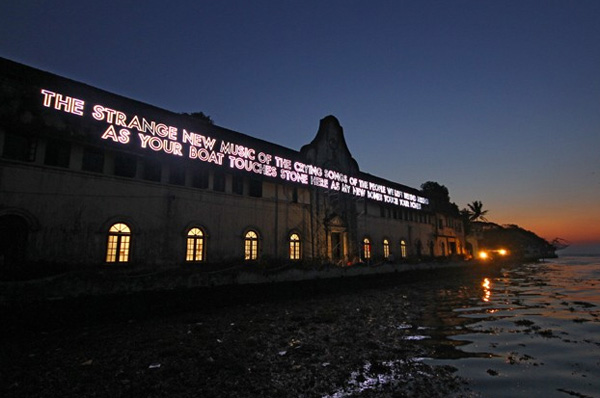

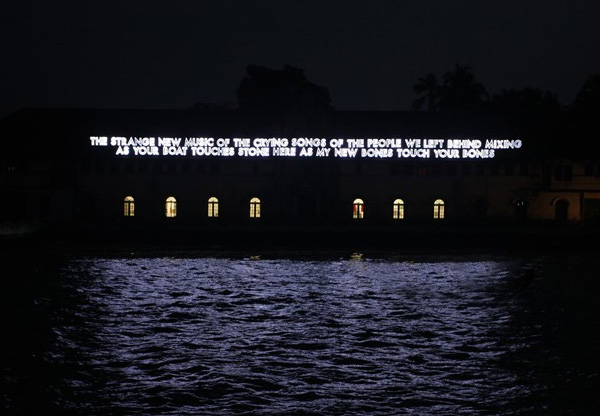

As an imaginary Fado song for sailors is how our first book artist Robert Montgomery imagined the words for his contribution to the first ever biennial in India – the Kochi Muziris Biennale, which also includes works by two other mono.kultur cover stars, Cyprien Gaillard and Ai Weiwei. Montgomery’s work was installed on the façade of a building facing the harbour across a span of 40 meters, as a posthumous welcome to sailors far from home.

As an imaginary Fado song for sailors is how our first book artist Robert Montgomery imagined the words for his contribution to the first ever biennial in India – the Kochi Muziris Biennale, which also includes works by two other mono.kultur cover stars, Cyprien Gaillard and Ai Weiwei. Montgomery’s work was installed on the façade of a building facing the harbour across a span of 40 meters, as a posthumous welcome to sailors far from home.

As an epilogue to last summer’s epic Echoes of Voices in the High Towers bonanza, by the way, his light installation All Palaces Are Temporary that graced our book launch venue at Stattbad Wedding has found a new home in Berlin and will be unveiled above the entrance of c/o gallery at the former Postfuhramt in Mitte (c/o, on the other hand, have finally found a happy solution to their tragic two-year-search for a new home, as a move to the legendary Amerika Haus in West Berlin has finally been confirmed, and congratulations for that!).

Last but not least in our little round-up, Montgomery also appears in the recent arts issue of our friends at Huge magazine in Japan – with the cover graced by none other than Michaël Borremans – for which we provided a brief interview with Robert, which you can read here and now:

On July 7, two light installations started radiating their gentle light on the edge of Berlin’s historic Tempelhof park, to be seen from the nearby street or the wide fields of the landing strip of the former military airport. ‘ALL WOUNDS EXPLAINED HERE, ALL HEARTS UNBROKEN’ read one of them. As summer progressed, more and more anonymous messages went up all around Berlin: over 20 billboards scattered across the city and posted in between advertising, or undefined pages in various magazines, all with white text on black ground, that did not want to sell you anything, but instead spoke of life in our day and time, of discomfort with our obsession with celebrities and material goods, of politics and Berlin’s fragmented past, but also of these little moments of magic that appear every now and then and when we least expect them. They were short and mysterious messages from nowhere that spoke directly to us instead of at us. They were the works of British artist Robert Montgomery and part of his largest project to date, Echoes of Voices in the High Towers, that slowly unfolded over the summer in Berlin.

Robert Montgomery writes poetry – and then inserts his words as art works into public space, in the form of light installations, billboards, magazine pages, fire poems, sometimes also as drawings or water colours. He does not sign his work, and so it is not instantly identifiable as ‘art’. His pieces come and go, you never know when or where they will appear next. In the end, what remains are images of the pieces that then experience a similar unpredictable trajectory on the Internet. There is a fleetingness and lightness to his work that suits his medium of words so extremely well – thoughts and associations that drift in and out of consciousness.

Robert Montgomery might be considered a fine artist, or he might be considered a poet, and maybe it doesn’t really matter which category he fits in best. What matters is that his poetry comes straight from the heart, that there is a personal urgency and investment that is immediately palpable and magnetic, very much in the same way his light installations will shine across the landscape at night.

You work as a fine artist, and yet you only work with words. What is the power of words over images?

There’s a long tradition of modern and contemporary artists using words going back to the Dadaists’ first experiments, although I guess I am probably an extreme example of it. Words have the power to assemble metaphors more quickly, and create pathos more sharply I think.

And yet, you always present your poems as works or images rather than ‘just’ words. Do we require the visual impact in order to pay attention to the words? Or why did you decide to publish your poems as visual pieces rather than publishing them in books?

I like the relationship of the physical or visual elements of my work – the light sculptures, the billboards, and the words they contain. It’s like having different instruments to play – you know, if I was to make an analogy to music, like vocals with guitar, or like piano and voice.

When did you start working with text?

Right from the beginning of my work, when I was at Edinburgh College of Art in the 1990s. I studied painting, but I can’t remember a time, even as an undergraduate, when my work didn’t have words in it, and I guess the words gradually took over.

There is a heritage of artists working with words, such as Jenny Holzer or Lawrence Weiner – do you see yourself in that tradition, and in what way does your work differ?

Yes, I see myself as exactly in that tradition, and those are two of the older artists who inspired me most. My work might be a little different in that it takes in certain places a step closer to modernist poetry.

How do you work on your poems – is it a concentrated effort, or is there a lot of editing involved? Do you have a practice of continuously writing poetry, or is it a more focused process towards specific pieces?

Both really, I write a certain amount of work the whole time as notes, which I’ll work up for billboards or condense for light pieces. For big projects, like Echoes of Voices in the High Towers for Berlin this summer I’ll start from a specific place or context or the history of that place.

You work in different media – billboards, light installations, fire poems, but also drawings and wood panels. How do you determine in which media you present your poems? Do the words come first or is it vice versa?

The writing is in a way the core underlying practice, and I’m constantly thinking, ‘Would this work as a light piece, would this work as a woodcut piece or a water colour?’ Often I’ll start with a billboard work and then condense that text for a light piece or adapt it for a woodcut or water colour.

Your works contain a long and laborious process – which stage do you enjoy the most?

Taking the picture at the end! No, not just that. Actually I really enjoy the long meditative process of the water colours, each water colour takes 30 hours or more of very focused neat work. You can lose yourself in that process, let your mind float off, a little bit like mediation.

Many of your pieces are produced for specific events or moments – like the Jubilee Poems or the Oscar Night Poem. Can you describe what makes you want to react to these occasions?

I don’t know really, with those examples I like to take alternative positions on big, spectacular public events, look at them from a different perspective, critique them somewhat.

You present your works as anonymous gestures in the public space – as light installations or billboards – so they are not instantly readable as ‘art’. What are you hoping to achieve by that?

Two things really – the first is a practical one, simply to reach a wider audience, beyond the immediate specialist art audience. The second is that it means something of course, within the discourse of conceptual art, to present the work in that way. It means something both within and outside of the art discourse.

In what way is the environment important for the content of a piece? In what way do the words you wrote for Echoes of Voices in Berlin differ from works you did specifically for London or New York?

I hope the work I made for Echoes of Voices was particularly intoned by the feelings I have for Berlin. I hope it reflected the creativity and freedom I feel the city has now, as well as memories of its history. I hope that project was a love poem to Berlin in a way.

You sometimes show the same piece in different environments – how does that influence the content of the work, and are there works you wouldn’t show in a particular context, for instance a specific country?

Yeah, I have to think before I move a work to a new place, run it through in my head and see if it still works in that place. The thing to check is if there is a fact of the locality, a piece of local history for example, that could imply a meaning to the text that I didn’t intend. There are pieces I’ve felt wouldn’t move well to a particular place, and in that case I just haven’t done the projects or moved the pieces.

Your work is mostly temporary – the billboards are taken down again, the light pieces are usually for a limited amount of time, and the fire poems go up in smoke. In what way is time essential to your work?

I don’t know. I guess I must like that there’s a certain impermanence to most of the work, that it is a fleeting statement. A billboard piece is a temporary poem in the world that’s remembered only in a picture. All that’s left is the memory of a poem on a faraway street, and I like that.

Your poems are intensely personal while addressing very universal subjects. Does your relationship to the words and works of the past change over the years? Do they remain as relevant today as when you made them?

I’m sure not all my texts will remain as relevant to contemporary questions in 100 years, it would be improbable if they all did, but I hope some will. I’m not old enough yet to take that kind of retrospective perspective on the work yet I don’t think, and I’m kind of too immersed in doing it, and I also feel that I shouldn’t second guess it too much, I feel like I should just have a bit of courage and say it as I see it.

Your work seems to oscillate between the personal and the political, between hopeful and melancholic. Is that a conscious choice or simply determined by your personality and interests?

That’s a conscious choice. I’m interested in seeing how much I can mix the personal and the political, the hopeful and the melancholic. That’s a pretty good summing up of what I’m trying to do actually.

Why would someone want to make art in the first place? Where do you see your purpose as an artist?

I have one answer to this question that I like – the purpose of art is to touch the hearts of strangers without all the embarrassing trouble of having to meet them.